She had been a nurse at the big house during the Great War. That is where she had met him. On the surface, it seemed straight forward except for the complications: he was married and she was engaged.

The war had changed everything, for everyone. Some found that they were stronger than they had imagined, while others had lost their minds. Perhaps her behaviour had been a little of both.

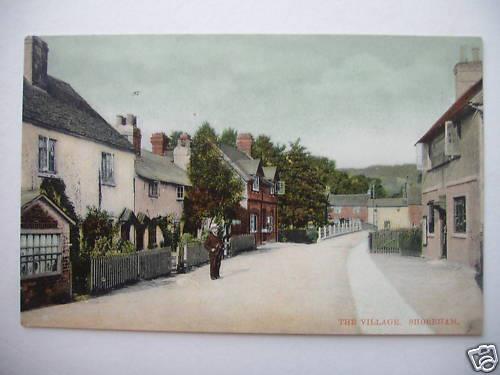

Neither of them had come from this little village but both of them had fallen in love with it, as they had each other. Her name was Helen Trent, and she had lived most of her life by the sea in Whitstable. He, on the other hand, had travelled with the army and considered nowhere and everywhere as home.

Nursing hadn’t been her first choice of career, she had always seen herself as a star on the London stage. But the dark winds had blown in from Europe and people had to do what they must, to keep the home fires burning.

He had improved in health – this was her job, patching up the sick and wounded and sending them back to be shot at again – they had found themselves growing closer. Then that awful day arrived when he was to return to the Front.

They took one last walk down from the big house to the bridge over the river.

He promised her that if he survived the war, they should meet up again and she agreed. Within the first few weeks of their separation, she broke from her engagement to Peter, a decent enough chap who had been chosen and approved by her parents. Peter didn’t seem that concerned, folks were getting married or separated all the time during the war years. They shook hands and parted as friends.

She received several letters from her love in which he wrote to say that he would tell his wife that she should divorce him on account of his adultery. He warned her it would be messy but everything these days was messy, thought Helen as she read the letter for the umpteenth time.

Then she lost touch with him. The love of her life was missing in action. She was sure he wasn’t dead, because she felt she would have known in her heart if that were true.

Yet the weeks, and then the months passed and there was no letters. If he were dead, they would have sent the sad news to his wife, and not to her, not to Helen.

Perhaps he had returned to his wife, perhaps he had come to his senses and perhaps he had fallen out of love with Helen. She was certainly still in love with him.

And then the years passed.

And then one day when she was back in Kent, she decided to visit that little bridge over the river, in that beautiful village of Shoreham.

It was 1930 and so much had changed in the world, but very little had done so in this little jewel in England.

And she looked down at the river, she smiled to herself because she was happy.

It was while she was doing this, that he had taken the photo. You see, he had come home and he had told his wife and now Helen and her soldier were married.

This was his photo of her. :-)

“Bertie is, as Bertie does”, was what my Auntie Clara used to say just before she would laugh so hard that a bubble would form at the bottom of her nose. Then she would hold her sides and say, “one more laugh and I might just wet my knickers”.

Uncle Bertie had always been the crazy one of the family, or as my mother – his sister – would say, “one day the will lock him up, I swear to God, and throw away the key”.

His first foray into attempting to get to the Tower of London was the day of Queen Victoria’s funeral. The village of Shoreham was understandably sad, and Uncle Bertie decided to dress up as a young Victoria and parade up and down Church Street.

One spinster, herself called Victoria, was so shocked by what she saw through the window, that she took the vapours and lay in a darkened room for several days. It didn’t seem to worry the family just how well Uncle Bertie portrayed a woman, and a royal one at that.

It was in 1906, that Uncle Bertie and Aunt Clara became custodians of the Kings Arms local hostelry. Aunt Clara’s father had made money in some South African mines and had left his wealth to her (he thought Uncle Bertie ‘a buffoon’ and made sure all the money was in his daughter’s name).

Although there was much competition in the village with the public houses, namely The George, The Rising Sun, The Royal Oak, The Two Brewers and last, but not least, The Crown, they still managed to make a living.

People came in from Swanley and Bromley to see Uncle Bertie and Aunt Clara behind the bar. Sometimes Uncle Bertie would get so drunk that he’d get Aunt Clara to play her fiddle while he danced naked on the table.

Uncle Bertie was forever getting into trouble.

When Christopher Landtrap came to stay in the village, he chose the Kings Arms as his drinking den. He brought down many ‘artistic’ London types who would quaff ale and sing songs down by the river. Christopher claimed to be a grandson of Salmuel Palmer, the Shoreham artist, it was neither proved, nor disproved but Shoreham being Shoreham, no one disputed the fact.

It was early in 1910 that Christopher got caught up in the photography bug which had spread among the bright young things. Christopher decided to make a record of all the public houses in Shoreham and that he would start with the Kings Arms. Uncle Bertie asked Christopher how long it took to take a photograph and he told him that it would take sixty seconds. So when Christopher asked everyone to stay indoors while he took the photograph – everyone did – except Uncle Bertie who ran into the street just as the photo was being taken.

The photo stands today.

Uncle Bertie died in London when a Zeppelin dropped a bomb in the street where he was walking and Auntie Clara died as she listened to Elvis Presley on the radio.

bobby stevenson 2016

Other Shoreham,Kent Stories http://shorehamkent.blogspot.co.uk/

or why not visit – you’d be made very welcome…

No comments:

Post a Comment