Tommy was tired of waiting for his life to start.

He

had given it more than enough chances in his nineteen short years,

thank you very much, and still there was nothing to get excited about.

So Tommy thought he might as well begin his life without any help from

anyone.

His

current dream was to watch the World Cup football final at Wembley and

if something was going to happen, it was going to happen there. After

all that was London, it was 1966 and it was most certainly the place to

be.

Tommy

had made a list of some of the people he would probably meet: Julie

Christie, Mick Jagger, Jean Shrimpton and Terence Stamp for starters.

He’d seen all of them in newspapers and all of them seemed to like

walking down King’s Road, Chelsea on a Saturday.

There

was just the small matter of earning enough money to get him south and

the small matter of keeping a roof over his head when he got there.

After

his Grandfather had passed away, Tommy was given the choice of any

piece in the old house. He settled on a small, beautifully carved,

wooden box that once held his Grandfather’s pipe tobacco and a

watercolour of the hills above the village, painted in his Grandfather’s

own hand. These would be the two possession he would take with him to

start his life.

To

raise the cash, Tommy worked on Sid’s farm from sun-up until dusk, then

at Bella’s cafe until nine at night, followed by the Climber’s bar

until one in the morning. When he had finished, he would deposit all of

his day’s earning in the beautifully carved tobacco box and collapse

onto the bed. By the morning, he was like a new man and would be itching

to start all over again.

The

day he left, was just like any other one, he awoke with the sun rise

and decided to slip away before the rest of the family rose. It was

easier that way. He lifted his rucksack and prepared to walk the twelve

miles to the railway station.

The

weather was kind and he arrived with plenty of time to spare. Tommy

decided to spend a couple of his hard earned pennies on a cup of tea but

anything as frivolous as a cake was not to be entertained. He reached

into his sack and discovered that his mother had packed several

sandwiches in a brown bag. He smiled to himself. They were his

favourites – all filled with cheese and onion, and as he lifted one out

to take with his cup of tea, a note fell from the brown paper bag.

It said “You can’t start a life on an empty stomach. Love Mum”

There

were enough sandwiches to feed a small army and would easily keep Tommy

satisfied on the journey south. He couldn’t remember mentioning he was

going to start his life to his Mum but that was mothers for you. They

knew everything, sometimes before you even knew them yourself.

The

journey was perfect as he sat eating his sandwiches and watching the

well remembered hills getting swallowed by the distance.

The

train whisked through towns with black smoke and cities with grey

people but the nearer he got to London, the more excited he became. He

knew he was going to start a life and that made him happier than

anything else he could imagine, even more than the inflatable Yogi Bear

he had received on his fifth birthday.

When

he opened the train door he could actually smell London and it spoke of

streets of dreams, and hopes and people that would become his friends.

He felt as if he already belonged, and although there was no one there

to meet him, it seemed as if everyone was there to meet everyone else.

What a place to start a life and what a place to call home.

He

spent the first night in a small hotel near Victoria station. It was

run by an old woman, of maybe forty years of age, according to Tommy.

She insisted that he call her ‘Twiggy’. He’d never seen such an old

woman wear such a small revealing dress.

“We calls it a mini skirt in these parts, young man”

Tommy

thought it was a very fitting name for such a short skirt. He mentioned

to the old woman that he was in London to get his life started and all

Twiggy would say was “Fancy that”.

At

Breakfast, Twiggy was wearing an even shorter skirt than the night

before and there were several business men in the lounge who kept

dropping knives and forks so that Twiggy would bend over.

Tommy

asked some of the men if they knew where he could get a ticket for the

final of the World Cup. All of them, without exception, started

laughing. “Oh, that’s a good one”, “That’ll keep me chuckling all day.

Thanks lad”, “Aye, thanks”.

The

door closed behind him asTommy stepped into the London street still

hearing the laughter from the Breakfast room. What was so funny about

what he had asked?

There

was now two days until the Final; surely someone was willing to sell

him a ticket? To be honest he didn’t really know where Wembley Stadium

was. “Somewhere in the north of the city, or the west” was how his

brother had described it. So Tommy started walking. He felt it was best

to avoid buses and The Underground until he knew London better.

Within

an hour, he’d arrived at Camden Lock and this place was alive with

music and flags and laughter. It appeared to be the centre of the world

for celebrating England qualifying for the Final. There were parties in

windows above him, people on roofs dancing. A conga line made up of a

dozen or so very happy people came out of a bar, slithered its way

across the road and into a bar opposite. All these people, thought

Tommy, had already started their lives and this made him grow even more

excited to start his.

As

he neared Kentish Town, he noticed a small cafe on his left. The place

smelt of coffee, looked as if it was in Morocco and had the mellow

sounds of jazz drifting out through the door. This was heaven.

When

the waitress served him his coffee, he thought he had been given the

wrong cup, “Excuse me, but I think someone may have already drunk from

this”

There

was only the smallest amount of coffee at the bottom of a very tiny

cup. The waitress smiled and moved on. Tommy noticed people piling sugar

on top of the coffee and so he did the same. He shouldn’t have

swallowed all the contents at once; he realised that the moment he went

dizzy,

“You okay man? Like, are you cool?”

The question came from Herbert, who spoke with an American accent but really came from the east end of London.

“Here, try one of these” said Herbert “Just call me Herbie, all my friends do” and he handed Tommy a French cigarette.

“I

don’t smoke” said Tommy. “This ain’t smoking, this is living” said an

agreeable Herbie. So if it meant his life would start sooner rather than

later, Tommy decided to smoke a cigarette.

Before he knew it, Tommy was lying on the floor - apparently in a room above the cafe.

“We

carried you up after you passed out” said the ever present Herbie. “I

guess the cigarette was too much man and maybe the coffee, man. You got

to take that coffee wisely, man. It can floor a buffalo”

Tommy

wasn’t sure if his life had now officially started, or he had just

pulled into the side of the road to let the rest of the traffic go past.

“Where’s my bags?”

“What bags?”

“I didn’t see no bags, man. Too many people carrying too many bags in this life”

Tommy

shot woozily out of the room and down a very narrow staircase before

slipping the last few steps into the bar and crashing on to the floor.

He

could hear a girl in the corner say “That’s the second time that man

has landed on the floor, what do they put in the coffee here?”

By

the time Tommy got back up to the room, Herbie was dancing naked on the

kitchen table to Highway 61 Revisited. Tommy’s bags had been stolen

along with his money and his chance of ever seeing the World Cup final

at Wembley.

Naked Herbie asked Tommy “What World Cup Final, man?”

So

Tommy and Herbie became the best of pals. Tommy stayed in Herbie’s room

but kept his clothes on at all times, unlike a lot of Herbie’s other

friends; Herbie’s room seemed to be the place to get naked in Camden.

England

won the World Cup and that made Tommy happy. Herbie gave Tommy some of

his shifts in the Cafe downstairs which let Tommy start to save some

money again.

One

evening in October, after Tommy had just finished working twelve hours

in the cafe, he heard a sobbing from the room, when he entered there was

Herbie crying his heart out.

Tommy

put his arms around Herbie and held him. Maybe it was one of his family

that had died but Tommy had never heard Herbie this upset before, even

the day he’d cooked the breakfast naked.

“It’s this, man” and he showed Tommy the newspaper. “All those beautiful children”

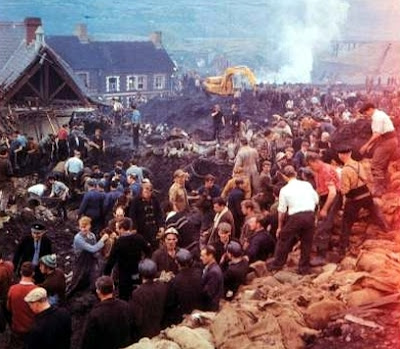

In

the Green Hollow Valley in Wales, a mountain of coal mining waste had

slipped in the heavy rain and covered a primary school.“We got to go

man. You and me, we got to help those people. Those children” and Tommy

sat beside Herbie and they both sobbed into each other’s arms.

Tommy

had saved enough money to get him and Herbie as far as Merthyr Tydfil

and then they would have to walk the rest. It was dark by the time they

reached the village, but there were lights everywhere, all the way up

the mountainside. No matter how tired they felt they got to work right

away, digging the slurry that covered the school and the little ones.

Sometimes

you give up on the world, believing that everything is greed and bad

but now and again you can see the best of people even in the worst of

situations.

At

least several hundred children, teachers and parents were missing. The

slurry had slipped across the school and into the houses opposite. Tommy

was digging between the houses and the school and as he looked up he

saw Herbie carrying a child with a cover over the body. Herbie looked at

Tommy and his eyes spoke of a million things he had seen that evening.

Important

people came and went; The Queen, The Duke of Edinburgh and The Prime

Minster but Tommy and Herbie never once wavered from the digging. A

couple of times Herbie fell asleep but Tommy would notice and waken him

up again.

This

is not to say that the boys were heroes, everyone was a hero that

weekend. Everyone pushed themselves beyond what they thought they were

capable of, to release the little bodies. Herbie was told to take a

break and he reluctantly did so. He went over to Tommy and shared a

French cigarette and Tommy smoked it with him.

“I don’t think I can cry anymore” said Herbie.

A

bearded man stopped and asked if he could possibly have a cigarette and

Herbie invited him to sit. The man told them that his child had been

ill that day and had stayed at home with his wife. His other child had

gone to school and he had survived but the slurry had taken his home

with his two darlings.

“How does that happen?” he asked them, how indeed.

It

had been a long time since any child, or anyone for that matter, had

been brought out alive and although Herbie and Tommy believed they could

hear shouts for help, it was only the tiredness calling.

By the following morning 120 bodies had been recovered but many loved ones were still waiting to be found and brought home.

There

are times in your life when you know that something you have taken part

in or witnessed will change your soul. Tommy knew it. It didn’t make

him bitter, it just made him realise that we are each other’s keepers

and we are all in this together. Good and bad times.

On the Monday morning Herbie, dirty and exhausted, felt it was time they returned to the cafe.

“Who’s gonna make the coffee, man, eh?”

Tommy tiredly agreed and they started off hitch-hiking back towards Merthyr.

There

were so many cars, ambulances and trucks transporting everything back

and forth that getting a lift wasn’t so easy. Tommy decided the best

thing to do was split up and meet back at the railway station.

“I’ll have a Frenchie cigarette waiting on you man” was the last he heard of Herbie.

Tommy

sat at the station for several hours before he felt that something was

wrong. He tried the Merthyr Tydfil police station to see if maybe Herbie

had hitched naked and been arrested. It was just a thought to cheer

himself up. The policeman informed him that they were too busy and that

all missing reports were being centralised in Cardiff. He would be

better going there.

It

was Tuesday before he found Herbie’s body lying in the morgue. It

seemed one of the trucks taking slurry from the school hadn’t seen him

in the lashing rain. He had been hit and died instantly.

Tommy

got back to the room above the cafe on the Thursday and only then did

he weep. He wept for the children and for the parents and for his

friend, Herbie.

And

that is when he realised that you don’t ever wait to start your life.

It begins the very first day you are born. Tommy was living when he was

at home, he was alive when he was in the room above the cafe and he was

most certainly living when he was with his best friend Herbie. Tommy had

been alive all his life, he just hadn’t realised it.

So Tommy did something he’d never done before, he took off all of his clothes in Herbie’s room and stood naked.

“This is for you, my pal”

And somewhere out there, he was sure he could hear Herbie laughing.